Statue’s secrets – Kléber

May 7th 2021, by Remy

Strasbourg city center is home to some pretty statues. Yet the inhabitants sometimes pay little attention to them. Of course, as we pass by them every day, they are now part of our daily routines and we no longer see them… That’s quite a shame, because they have things to tell.

Today, let’s focus on some elements of the general Kléber’s statue, located on the eponymous square. For those who have already followed our Surprise Tour dedicated to those stone celebrities, it will be a little reminder; for the others, some kind of foretaste which may entice you to join one of our Free Tours when we have the right to go out again, or so I hope!

A renowned Strasbourg resident

Jean-Baptiste Kléber was born in Strasbourg on March 9, 1753. His wish was to make a career in the military and he enlisted for the first time in 1769. However, he was only 16 years old then and his mother had other projects for him: so back he came to resume his studies and become an architect.

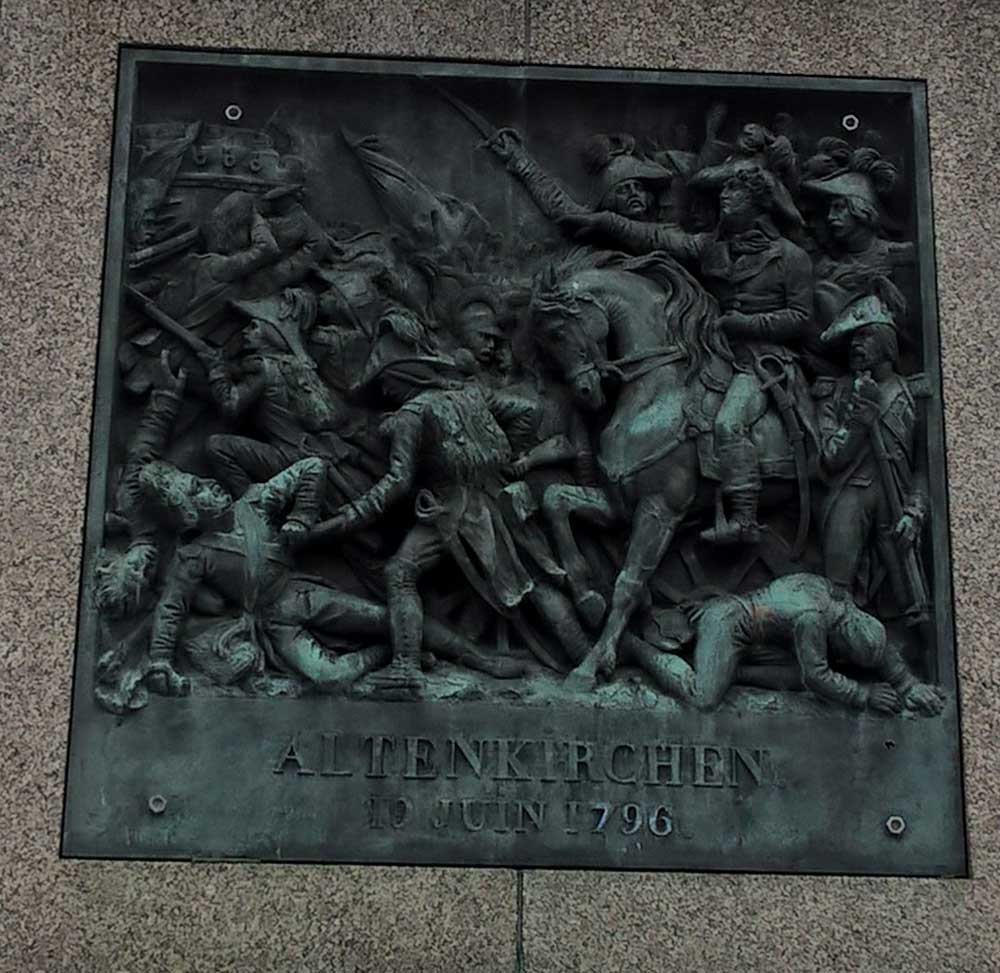

Never mind, he left again for the army in 1777 and ended up integrating the Austrian army. Time passed and the French Revolution shuffled all political cards: yesterday’s friends could become the next day’s enemies. Thus, the path of Kléber crossed again that of the Austrians in 1796 … this time to fight! This is the battle of Altenkirchen and the subject of the left bas-relief when facing the statue.

Despite his feats of arms, Kléber was no longer considered a key figure during the Directory (a governing committee in place from 1795 to 1799). He left the army again in 1797. That was before taking into account the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte. In his company, Kléber returned to arms one last time, as part of the French campaign in Egypt and Syria.

Once again, he distinguished himself, this time at the Battle of Heliopolis, represented on the right bas-relief.

At the end of this campaign, Napoleon returned to France (August 1799) and left the army’s command to Kléber. The British, on the lookout, were waiting for the first opportunity to attack the French. Kléber was not a crazy man and he seeked to get himself and his men nobly out of this situation. He negotiated the departure of the French troops with Admiral Smith (“the Convention of El Arish”). But another British officer, Admiral Keith, was not so keen about it and refused to honor the terms of this agreement. This brings us to that famous battle of Heliopolis, won by the French and which will evoke some more later on.

However, Kléber did not have the opportunity to savor his triumph for very long. On June 14, 1800, he faced his fate, in the guise of a Syrian student, Soleyman el-Halaby. The latter stabbed him to death. The legend of General Kléber was then to be associated with the land of pharaohs for ever. The small stone sphinx at his statue’s feet is as reminder of that fact.

The return of his remains to France was done in such a discrete fashion that his coffin was “abandoned” for 18 years at the Château d’If, near Marseille. He was not to return to Strasbourg until under Louis XVIII. Almost all his remains were then placed in a vault (situated beneath the statue) in 1838. “Wait a minute! What do you mean “almost all of his remains” ?!” That’s what you’re probably saying to yourself right now, I can hear you from here! Well, the thing is, as a military hero, his heart has the great honor to rest at the Invalides (military necropolis in Paris).

A charismatic leader of men

Kleber was not just anyone, if we are to believe Napoleon’s own words: “Courage, conception, he had it all […]. His death was an irreparable loss for France and for myself. He was Mars, the god of war incarnate.”

If it’s not enough to convince you, then let us go back to the Battle of Heliopolis, as promised. Remember: the desire for an honorable exit out of Egypt, an agreement found with the British, that was to be disrespected by Admiral Keith… See that little piece of paper held by Kléber’s statue in its right hand ? It is a note of sorts he apparently disliked to the point of making a pout for eternity… It is Keith’s demand to surrender!

Well, they knew very little of the general if they believed he would obey such a request. Only one way out was left: to fight to the bitter end. The French were clearly outnumbered (11,000 French against 40,000 Ottomans, allied with the British). But Kléber found the words that would lead them to victory. They are faithfully reproduced on the right bas-relief: “One can only answer to such insolence by victories; soldiers, prepare to fight”. The rest, you already know: one more victory for Kléber and death six months later.

A statue with an issue

The statue of Kléber was placed on its pedestal in 1840. It is the work of Philippe Grass, also the author of Adrien de Lezay-Marnesia’s statue and a specialist in the re-creation of statues destroyed during the French Revolution.

When the statue was inaugurated, 40 years to the day after Kléber’s death, we were in the midst of the July Monarchy. The French were looking for national unity, around strong and unifying symbols. We were aiming for reconciliation and Kléber, a hero of the Napoleonic Empire, was not the ideal candidate. We therefore drew attention to another statue, also well known to Strasbourg’s inhabitants: that of Gutenberg. Its inauguration came with great festivities and there even was an industrial procession, in which the city’s corporations took part. A way not to attract too much attention to the neighboring square and its less consensual statue of Kléber.

Does that mean that the statue of Gutenberg was not cause for any concern? Absolutely not, but to find out more, you will have to come and join us for a tour 😉